Four days ago, Norwegian chess grandmaster Magnus Carlsen faced controversy at the World Rapid and Blitz Chess Championships in New York due to a dress code violation. On December 27, he was fined $200 for wearing jeans, which were explicitly prohibited by the event’s regulations. When asked to change into appropriate attire, Carlsen refused, leading to his disqualification from the tournament. He defended his decision as a matter of principle, expressing frustration with the enforcement of such rules. The International Chess Federation (FIDE) agreed to relax the dress code, allowing “elegant minor deviations,” including appropriate jeans paired with a jacket. Subsequently, Carlsen returned to the competition and, in an unprecedented outcome, shared the World Blitz Championship title with Ian Nepomniachtchi after a series of tied games.

Coach Eluekezi Phoenix Chkwuwikeh writes from Lagos, Nigeria

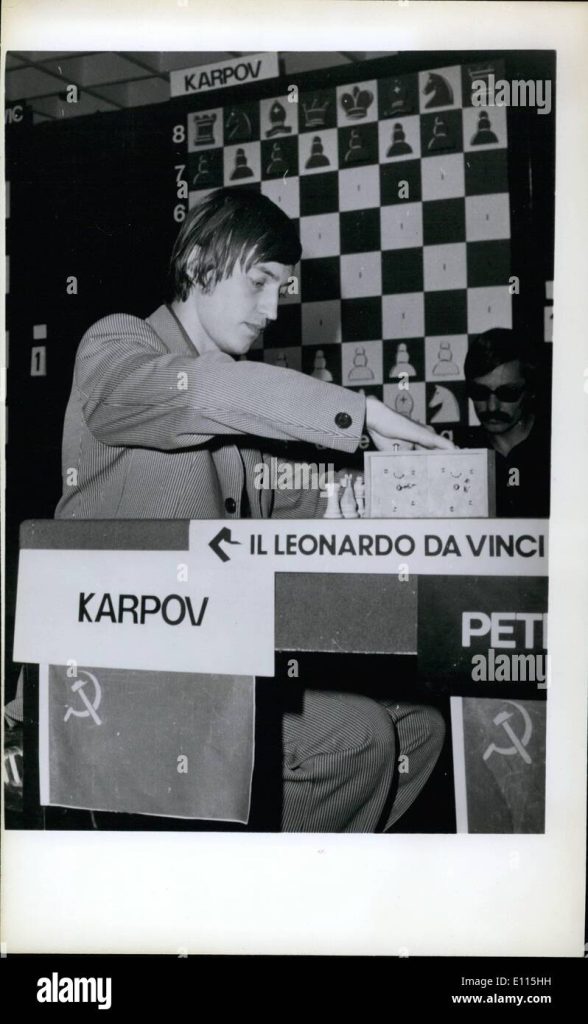

In 1984, the rules for the World Chess Championship match between then-defending champion Anatoly Karpov and 21-year-old challenger Garry Kasparov had the basic rule that the first player to six (6) wins would be crowned champion. After the first nine (9) games, Karpov had five (5) draws and four (4) wins! At this point, it was somewhat embarrassing and had the trappings of annihilation waiting to happen. Most other elite players at the time had predicted a win for Karpov within twenty (20) games. However, Kasparov dug in and there followed 17 consecutive draws – hold my beer Carlsen-Caruana. Karpov struck again in Game 27 to go 5-0 up! At this point, Karpov needed just a solitary win to retain his title. After four (4) more consecutive draws, Kasparov finally beat Karpov for the very first time in his life in Game 32 of the match. I must state at this point that Karpov, during his reign as World Chess Champion, was both prolific and ruthless. To date, despite the impressive exploits of his brilliant successors, he still holds the record, and by a mile, for the highest number of 1st-place finishes in elite tournament chess history!

With the score now at 5-1 in Anatoly Karpov’s favor after Game 32, there followed fourteen (14) consecutive draws. With today’s format, Karpov would have won the match a long time ago, but the match had now stretched into months as Karpov, after nineteen (19) games since his last win, failed to deliver the fatal blow. In Game 47, Kasparov won again and won the very next game, too!

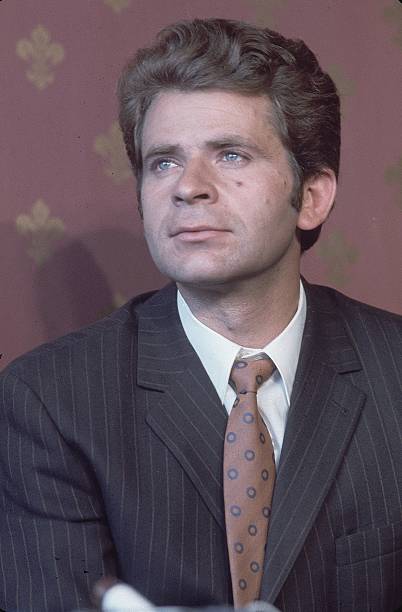

FIDE President at the time, Florencio Campomanes (who served from 1982 till 1995 in that capacity), called off the match and rescheduled for months later with a more limited format, with a fixed number of games, closer to what we have these days, and that had also been used several times prior. Both players protested and wanted the match to continue, but Campomanes would have none of it. He claimed the match had dragged on for way too long and that he had to consider the health and well-being of both players. It must be said that at this point, Karpov was “visibly smaller.”

Kasparov trailing by 3-5 seemed the more aggrieved and protested more loudly. He claimed Campomanes ended the game to prevent him from eventually winning the match, citing that he was the one on the ascendancy. Well, let’s say he had to wait till 1985.

Shortly after eventually dethroning Karpov months later, Kasparov formed the “pressure group” Grandmaster Association (GMA), which targeted giving elite chess players more say in FIDE’s activities and adopted tournament cycles and formats. An activist had been made of him!

Kasparov was famously quoted as saying, “Campomanes must go. It is a war to the death with him as far as I am concerned. I will do everything I can to remove him.”

Campomanes did have the last laugh; or did he? In 1993 he stripped Kasparov of his title and and expelled Kasparov and his challenger, Nigel Short from the official FIDE rating list after they both decided to play their World Championship Match outside the auspices of FIDE. This wasn’t exactly a completely novel occurrence, but it was definitely way more dramatic and elaborate than any such preceding event. FIDE organized a match between Anatoly Karpov and Jan Timman who were next in line (3rd and 4th) based on the qualification process. The Dutch were delighted, but Kasparov had managed to piss all over their cake.

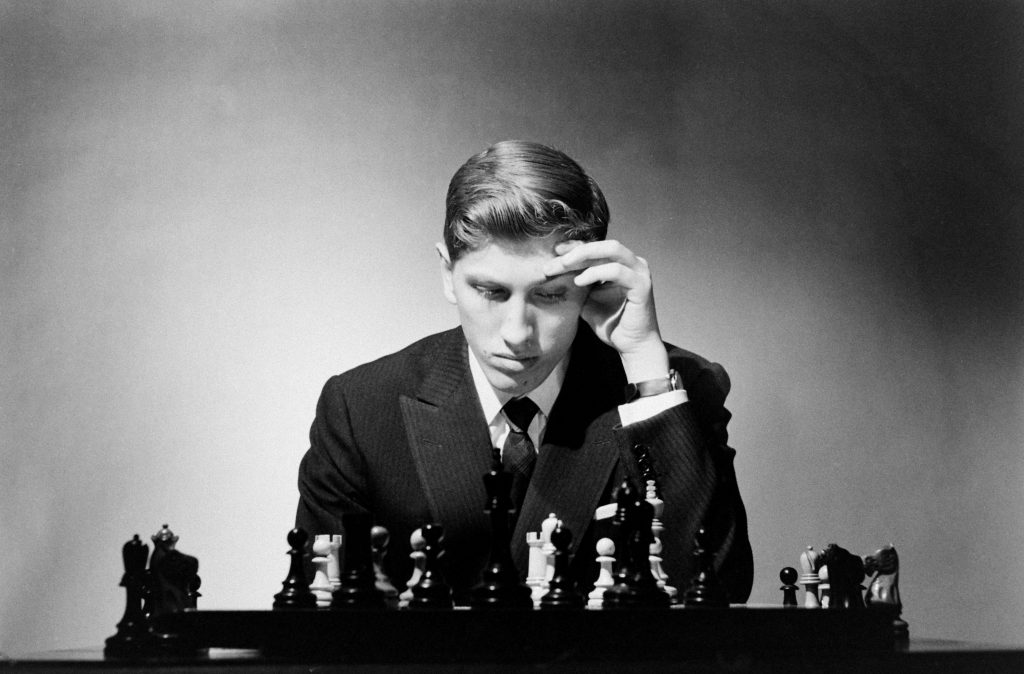

History repeated itself when Karpov won the Karpov-Timman match to become FIDE World Chess Champion again. Karpov had now twice benefitted from a sitting world chess champion losing his title without having to play against them. Eighteen (18) years earlier, in 1975, Karpov had become champion without having to push a single pawn against Robert James Fischer. Unlike Kasparov’s tantrums, Bobby Fischer had gone relatively quietly into the night.

Interestingly, in 1992, whilst Kasparov was still World Chess Champion, having successfully defended his title twice against the now ubiquitous Anatoly Karpov in 1987 and 1990, an alternate World Chess Championship match was organized in Iceland between former World Chess Champions Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer – a rematch of their 1972 match twenty (20) years earlier. At the time, this rematch had the biggest purse of any World Chess Championship match in history at $5 million, with the winner receiving $3.35 million and the loser receiving $1.65 million.

Photo Credit: Carl Mydans The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

I know I am now pushing it, but if you raised an eyebrow for me sounding like it was a legitimate World Chess Championship match, then you must, in equal measure, point some scorn the way of the notion that the World Chess Championship match held in London in the very next year by the FIDE-ostracized Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short had any legitimacy whatsoever. You would also have to spare some scorn for the other three (3) PCA (Professional Chess Player’s Association) sic Classical World Chess Championship matches held outside the auspices of FIDE in 1995, 2000 and even the 2004 Kramnik-Leko match.

In the aftermath of the Gukesh-Ding match, which ended rather anticlimactically in Gukesh’s favour, there have been numerous headlines and captions in the order of “Youngest Ever Undisputed World Chess Champion.” If these ubiquitous headlines and captions aggravate me so much, then I can only struggle to imagine the anguish Ruslan Ponomariov, who had to best 127 other elite players in one of the most grueling World Chess Championship formats ever, must feel. It was a knockout format that started with 2-game matches (with rapid then Armageddon tiebreakers) with an increasing number of games per match as one advanced. Was all that for nothing? For no fault of his and in absolute compliance with the rules of the world governing body, he got tossed aside in history for a “protest line.”

I had to include some of the facts above for context, especially for much younger readers who didn’t have the option of observing these events in “real-time.” History has been altered and twisted over time by subtle, persistent propaganda.

It is pertinent now to point out that many elite players at the time were seriously opposed to the knockout format adopted to select the World Chess Champion, but FIDE persisted for four (4) cycles, resulting in the following World Chess Champions:-

1. Alexander Khalifman – 1999

2. Viswanathan Anand- 2000

3. Ruslan Ponomariov- 2002

4. Rustam Kasimdzhanov – 2004

FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Echecs) has been in existence for over a century now, and for the most part of that time, they have been the sole moderator of the World Chess Championships and have been the official world governing body for chess. Prior to this era, World Chess Championship matches were usually mainly sanctioned by the reigning champion, who set conditions for the match and his challenger and only played if his personal conditions were sufficiently met. Alexander Alekhine, for instance, made it practically impossible for his predecessor, Jose Raul Capablanca, to get a rematch. He preferred rather to play clearly weaker contenders, one of whom shocked him, in Max Euwe, snatching the title from 1935 to 1937.

When Kasparov initially formed the PCA, they had very elaborate and rigorous qualifiers that ran for months to select the challenger for the 1995 edition. However, by the time Kasparov attempted to defend his title in 2000, the selection process was at best shambolic as he practically, more or less, handpicked Vladimir Kramnik.

Kramnik is somewhat an anomaly in the post Botvinnik era, as he is the only World Champion in that time without a credible selection process.

After the death of the then reigning Champion, Alexander Alekhine in 1946, FIDE decided to organize a double round-robin World Championship match between the five (5) eligible contenders by their own estimation—Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasily Smslov, Paul Keres, Samuel Reshevsky and Max Euwe, who was a former World Chess Champion and a future FIDE President. Jose Raul Capablanca had died a few years earlier in 1942. Mikhail Botvinnik emerged victorious, but not without controversy, as the “outsiders” Reshevsky and Euwe had very good reason to suspect collusion amongst the Soviets.

That line of succession from Botvinnik, who had to fight back to regain his title more than once, led directly to Gukesh D., or so it seems. In 2006, FIDE’s official World Chess Champion, Veselin Topalov, was made to play a Reunification Match with the “Classical World Chess Champion”, Vladimir Kramnik in a bid to assimilate the rogue arm. Even those who held the opinion that the PCA/Classical Champions were illegitimate, had to admit, after Kramnik’s triumph over Topalov in 2006, that Kramnik had earned his spot on the line of succession. What is still up for debate is if he gained that right in 2000 or 2006. I still remember the outrage when former FIDE President, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov repeatedly called Vladimir Kramnik the “14th World Chess Champion” after the match. The ilk of Ponomariov et. al were visibly and rightly incensed.

It is unconscionable to trivialize the achievements of others in a bid to legitimize yours. Kasparov, through deliberate and sometimes subtle persistent effort in his books, speeches, lectures, etc., over the years, chipped away consistently at FIDE’s credibility and succeeded in doing same to his peers. It is ridiculous to legitimize his line of succession to the extent of official acceptance by the same organization he tried to undermine for years and years, and to the detriment of hardworking chess players who had to earn their stripes by being compliant to the authority of the day and focusing their effort on just playing chess.

In 2003, Kasparov agreed to play a World Championship match against the then reigning FIDE World Chess Champion, 19 year old Ruslan Ponomariov. For context, Kasparov had been dethroned as Classical Chess Champion (formally PCA Chess Champion) in 2000 by his chosen challenger for the match, Vladimir Kramnik.

Kramnik was scheduled to play Peter Leko in 2004, after which FIDE had hoped to organize a Reunification Match between the winners of both events under the terms of the so-called “Prague Agreement”. Plans for the Ponomariov-Kasparov 2003 match eventually fell through resulting in Ruslan Ponomariov retaining his title for an extra year, while Kramnik had to wait 2 more years to play Veselin Topalov for the Reunification Match in 2006. The fact that Kasparov had initially agreed to this match against Ponomariov, in the first place, points to the fact that he was more interested in regaining his title than he was in FIDE’s credibility.

Last week, someone stated that Fischer, Kasparov and Carlsen are the strongest chess players that ever played the game.” He then went further to ask, “Why did they all have issues with the world championship formats.” My guess would be that it should not be rocket science to figure that one out – there is a degree of dominance one will have in a discipline or field of endeavour that automatically translates into influence.

Fischer is rightly credited for raising the average earnings of chess elite players by his many demands, which sometimes seemed frivolous and overreaching at the time. However, he had a pretty decent idea of what he was worth and usually put his foot down to get his demands met. Kasparov made a lot of demands too and when he pulled away from (or got kicked out by) FIDE to form the PCA, he managed to break prize money and sponsorship deal records for his 1993 PCA World Championship match against Nigel Short, and his 1995 match against Viswanathan Anand. Magnus Carlsen has been dominant for over a decade now and has also generously voiced out his displeasure with certain rules and formats for qualification and time controls for the World Chess Championships. Heck! Even Veselin Topalov, after Kasparov’s retirement from competitive chess in 2005, leveraged on his status then as FIDE World Chess Champion and as the highest rated player for a while, to make a lot of demands.

To be the best at chess, or any other thing for that matter, requires a lot of effort, dedication, and sacrifice. Those who make such input to get there know what it takes. It is little wonder, therefore, when they try to make certain changes when they reckon they wield significant influence. This is common in other sports and fields of endeavor, too.

In 1971, Robert James Fischer absolutely demolished the competition to win the knockout format for the Candidates match. Amidst a whirlwind of drama, he defeated the reigning World Chess Champion, Boris Spassky, to become World Chess Champion.

When then-rising star Anatoly Karpov beat Victor Kortchnoi in the Finals of the 1974 Candidates match, thus qualifying to play Bobby Fischer, the stage was set for an epic showdown. Tragically, Fischer made demand after demand, which FIDE struggled to keep up with. In the end, Fischer defaulted, and Anatoly Karpov was declared World Chess Champion in 1975.

Fast forward to 1993, Nigel Short had against all odds qualified via a grueling Candidate to emerge challenger to reigning World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov. Then came the complaints and demands. FIDE was not in the mood to make concessions. But this time, not only did the World Champion pull out of the match, but so did his challenger.

Magnus Carlsen made a few mild-hearted complaints and subtle protests, starting with his pulling out of the qualification process even before he was a challenger. After becoming a 5-time World Champion, he finally called it quits and decided not to attempt to defend his title. This left FIDE in an awkward position, and as always, chose the next in line from the Candidates to play the challenger, thus setting up the clash between Ding Liren and Ian Nepomniachtchi, which culminated in Ding Liren becoming World Champion.

All the above three cases are widely different, but the premise and subsequent decisions by FIDE are sufficiently similar to state at this point that FIDE is consistent in not bending, at least fully, to the whims of chess players no matter how highly placed.

It is, therefore, a wonder to me, as I believe it is to many others, why, in Kasparov’s case, his line of succession has now been officially adopted by FIDE.

If Fischer weren’t World Champion after his default in 1975 and after his rematch with Spassky in 1992, why would Kasparov have a claim to the title he was stripped of in 1993? Magnus Carlsen is clearly still the strongest chess player today, and maybe in history, he isn’t going around parading himself as World Chess Champion.

Ruslan Ponomariov became World Chess Champion at 18 years 3 months and 12 days old, a full three (3) months earlier than Gukesh D., who achieved the same at 18 years 6 months and 13 days. There is no legitimate dispute here, and it is just disingenuous to be part of those claiming Ponomariov isn’t the youngest ever World Chess Champion, whether you choose to include the word “Undisputed” or not!