“Chess doesn’t drive people mad – in fact, it keeps mad people sane”

Bill Hartston

A couple of weeks ago, on 23rd June 2019., popular chess streamer and content creator, International Master Anna Rudolf wrote an emotional Instagram post in which she described how she had been battling with depression in the preceding months.

I found her post incredibly brave and worthy of admiration. Even though a lot of progress revolving mental illnesses and mental health, in general, has been made in the last couple of decades, talking about depression and anxiety still involves a lot of stigma and is a sort of a taboo.

Ever since my friend wrote openly about his own battle against depression, I realized that the only way of destigmatizing mental issues is to talk about them openly. And to raise awareness that they happen on a much broader scale than most of us assume.

Especially in the world of chess. Despite Hartston’s apocryphal remark, Anna Rudolf is definitely not the first chess player to experience mental problems. Chess history is full of examples of players suffering from severe cases of depression and/or other mental issues. Sometimes these issues resulted in most tragic outcomes.

Of course, it would be premature to claim that chess causes these issues per se. The exact causes of depression and other mental illnesses are not exactly known. But as far as I know, 1 there is a strong genetic component involved. Chess in itself can’t be responsible for the appearance of mental illness if the person is not prone to developing one.

However, I do think chess might serve as a trigger. Tournament chess puts an enormous strain on the nervous system. I think this is especially apparent on the professional level when one’s existence depends on the outcome of the game. I am sure you all know at least one strong player (Grandmaster even) who is rather distressed and uncertain about his future. In his book, Russian Silhouettes, 2 Grandmaster Genna Sosonko summed it up quite nicely:

In our day top chess demands even more all-devouring preparation, complete concentration, and aloofness from everything else. In the future this tendency will only be intensified. Players will reach the summit and pass their peak well before thirty. Too much nervous energy will have been spent on preparation and struggle in the younger years. Giving the joy of creativity, and sometimes prizes and money, chess at the very highest level demands a trifle in return – the soul.

So, even if chess can’t cause mental illness in itself, I think it makes more likely to appear.

12 CHESS PLAYERS WHO SUFFERED FROM SEVERE MENTAL ILLNESS

In the remainder of this post, you will find a list of chess players who suffered from severe mental illness.

I have to mention I refrained from including Robert James Fischer (because he was never officially diagnosed) or Paul Morphy (whose family tried to put him into a mental institution but he refused to go). I also refrained from including Raymond Weinstein (a young and promising American International Master who murdered an 83-year-old man) or Alexander Pichushkin (a serial killed known under the nickname „Chess Killer“), since I wanted to focus more on the depression/anxiety and less on psychopathic/sociopathic side of mental illnesses. More about Weinstein and Pichushkin can be read in the links provided under References.

With that being said, without further ado, I present you a list of 12 chess players who suffered from severe mental illness.

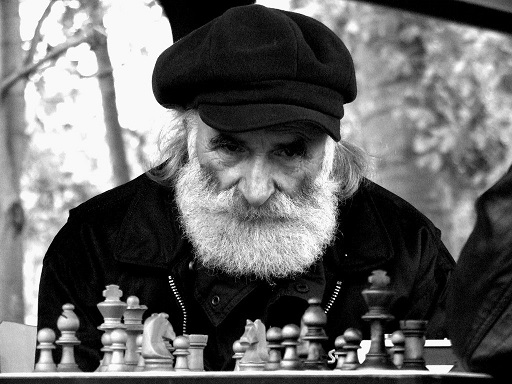

1) Alvis Vitolins

Alvis Vitolins (Source: Douglas Griffin Twitter)

I will be honest. I first got the idea to write this post when I first read the afore-mentioned Sosonko book Russian Silhouettes, before I saw Anna Rudolf’s social media post.

More precisely, the chapter about Latvian Master and Tal’s trainer/sparring partner Alvis Vitolins left an indelible impression on me. Vitolins was an extremely promising player in his youth, but he never realized his full potential. Sosonko thinks it had a lot to do with a serious mental illness Vitolins has been fighting against throughout his entire life:

[…] to understand fully the phenomenon of Alvis Vitolins, one has to know that he suffered from a severe mental derangement. Effectively from the very start, he was not so much battling against his opponent as against himself.

Even though he was treated by a psychiatrist friend for free and prescribed anti-depressants, Vitolins’ story had the most tragic outcome. At the age of 50, he decided to take his life by jumping from a bridge to Gauja river. In Sosonko’s words:

While his parents were alive this was their concern. They died within the space of one week, and on New Year’s Eve 1996 the psychiatrist Eglitis, also a chess player, who had been treating Vitolins for free, also died.

[…]

In addition, he had reached the age of fifty and at this stage of his life he must have felt that he was no longer needed by anyone.

[…]

He had never complained about this life, but also he did not want to remain in it any longer. Sigulda is one of the most beautiful places in Latvia. Mysterious sandy caves, the ruins of medieval fortresses and castles, an enormous park with ancient oaks divided by the swift-flowing Gauja with its precipitous banks.

It is also good here in winter, when all is snowy and the trees are covered in hoar-frost. When the only thing sparkling in the sun is the white-blue ice of the hardened river, and it beckons, beckons to you, and there only remains the last jump. Like Luzhin, who ‘at the instant when icy air gushed into his mouth, … saw exactly what kind of eternity was obligingly and inexorably spread out before him’.

[…]

On a frosty day, the 16th February 1997, Alvis Vitolins threw himself down onto this ice from the railway bridge spanning the Gauja river. 3

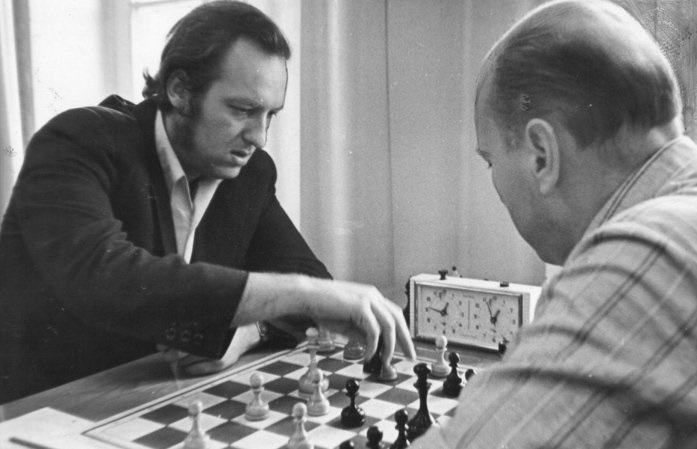

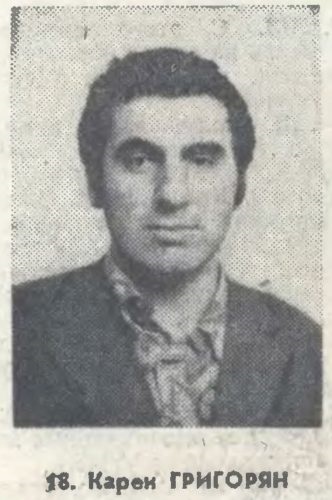

2) Karen Grigoryan

Karen Grigoryan (Source Alchetron)

Karen Grigoryan was an Armenian International Master with an equally tragic story. He battled depression throughout his life and in 1989 – at the age of 42 – he committed suicide by jumping from the highest bridge in Yerevan. From Russian Silhouettes:

The following day, after losing a game, he could become dejected and depressed, repeating that his own play was repulsive to him, that his life was of no use to anyone. He would begin talking about suicide, long before he became a patient at a psychiatric hospital and long before that final free-fall jump from the highest bridge in Yerevan on 30th October 1989.

Incidentally, Grigoryan and Vitolins were close friends and could be often seen together in tournament halls, isolated from the world around them:

The friendship between Grigorian and Vitolins was not a friendship in the generally accepted sense of the word. Shut off from the other world, they simply understood each other, or, more correctly, trusted each other. They intuitively felt that the other was a kindred soul, who after a conversation with you does not go off and begins retelling its content with an ironic smile.

As they say, birds of a feather flock together…

3) Norman Von Lennep

Norman Von Lennep (Source: Chesshistory)

Norman Von Lenne was a Dutch player from the end of the 19th century. Even though he came from an upper-class family and was expected to study, earn a title, get a good job and marry a nice young lady, he decided to become a chess professional instead. There are also rumors nice young ladies didn’t quite interest him as much as nice young men.

Due to his choices, his father decided to exile him. During the Hastings 1895 tournament where he worked as a journalist, it was announced he has decided to stay in England.

However, being abandoned by family and living in a foreign country among strangers apparently took its toll on his (fragile) mental state. In 1897, he took a ship sailing from Harwich to the Hook of Holland. During the trip, he jumped into the North Sea and ended his life at the shockingly early age of 25.

4) Curt von Bardeleben

Curt von Bardeleben (Source: Schachbund.de)

The name of Curt von Bardeleben is most often associated with a game from the Hastings tournament 1895 in which his opponent Steinitz executed a brilliant combination involving a series of consecutive rook sacrifices. 4

What I didn’t know is that Vladimir Nabokov’s book The Defence 5 was inspired by von Bardeleben. At the age of 62, he committed suicide by jumping out of a window – just like Nabokov’s main character, Luzhin.

5) Wilhelm Steinitz

Wilhelm Steinitz (Source: Unknown)

It is well known that Wilhelm Steinitz wasn’t the most successful when it came to managing his finances and that he died in poverty.

What is lesser known that he also battled with mental issues. I first stumbled upon it on his Wikipedia page, which claims that he spent 40 days in mental Asylum in Moscow after his 1896 match against Lasker, and also that he died in a mental asylum in New York.

I was able to find sources that verify it is indeed so. First of all, the book Wilhelm Steinitz: 1st Chess Champion states that in 1896:

“The decision was made to transfer Steinitz to a psychiatric hospital.”

More importantly, an article on the reliable source – the website Chesshistory – by Edward Winter, titled Steinitz versus God provides us with the following quotes from reliable sources:

‘As the years went by, he veered into a much more serious state of psychosis. For a time, he was confined to a Moscow asylum. He insisted that he had played chess with God over an invisible telephone wire. (God lost.)’

[…]

‘He died, impoverished, in a New York mental asylum following an unsuccessful attempt to challenge God to a chess match.’

6) Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Harry Nelson Pillsbury (Source: Chessbase)

Steinitz was not the only player from the end of the 19th century to suffer from a mental disorder. American hero Harry Nelson Pillsbury’s is an even more tragic example.

Pillsbury’s story is well-known. He shocked the chess world by winning chess tournament in Hastings in 1895, got overpowered by Lasker in St.Petersburg in 1895, continued playing for several years and then became seriously ill due to a syphilis infection, which cost him his life in 1906 – at 34 years of age.

His mental problems – a direct consequence of the rapidly progressing illness – are less-known. After he got hospitalized in 1905, contemporary newspapers described him as ‘temporarily insane’. According to yet another fantastic Chesshistory article, titled Pillsbury’s Torment, he even attempted suicide by jumping from the fourth floor of the hospital where he was being treated for mental disorders.

7) Akiba Rubinstein

Akiba Rubinstein (Source: Chessgames)

There are several accounts that the great Polish player, Akiba Rubinstein, spent his last 30 years regularly visiting mental institutions. According to his Wikipedia page:

After 1932 he withdrew from tournament play as his noted anthropophobia showed traces of schizophrenia during a mental breakdown.

In Russian Silhouettes, in the chapter against Vitolins, Sosonko mentions him as an example of a chess player who lost his sanity:

Vladimir Nabokov, who by his own admission took particular pleasure in composing ‘suicide studies’ – where White forces Black to win – said in an interview on French television: ‘Yes, Fischer is a strange person, but there is nothing abnormal about a chess player being abnormal, this is normal. Take the case of Rubinstein, a well-known player of the early part of the century, who each day was taken by ambulance from the lunatic asylum, where he stayed constantly, to a café where he played, and then was taken back to his gloomy little room.

He did not like to look at his opponent, but an empty chair at the chess board irritated him even more. Therefore in front of him, they placed a mirror, where he saw his reflection, and, perhaps, also the real Rubinstein.’ Even in the years of his triumphs, the great Akiba liked to sit half turned at the chess board, as though keeping aloof from his opponent and playing only his own game.

It has to be mentioned, though that Edward Winter seriously doubted all these claims in his article Akiba Rubinstein’s Later Years:

Much about the last 30 years of Rubinstein’s life is unclear or unknown, but it is evident that for most of that period he lived at home, and not in a sanatorium or mental institution.

8) Albin Planinc

Albin Planinc (Source: Unknown)

Even though it didn’t have the worst consequence, the story of Slovenian Grandmaster Albin Planinc is no less sad and tragic.

Planinc rose to prominence after winning the 1969 Ljubljana tournament, ahead of 10 grandmasters despite the fact that he was working shifts in the local bicycle factory. But he really shocked the chess world in 1973, when he won the strong IBM Amsterdam tournament, together with Petrosian – ahead of Spassky, Andersson, Donner, and Ribli. It seemed to everyone that great career was in the making.

Alas, Caissa had other plans. Starting from approximately 1975, an apparent mental disorder started taking its toll on Planinc. He was performing poorly and living in his own world, avoiding all social contact during tournaments.

In 1979, he played his final tournament before retiring from chess. I couldn’t find any information what he did for a living from that point onward. What is known is that he was living together with his mother in a small flat and constantly fighting his own demons.

He spent his final years in the mental institution in Ljubljana. According to the Slovenian biographical movie Total Gambit (Totalni Gambit), shortly after his mother died in 2008 – in the very same mental institution – Planinc also departed this world. His girlfriend’s words from the same movie, full of sorrow and pain, speak for themselves:

“We never stood a chance . . . Chess could not do it. How could I do it?”

9) Lembit Oll

Lembit Oll: (Source: thedeadones.wordpress.com)

Estonian Grandmaster Lembit Oll is a better-known name on this list and, unfortunately, the highest rated player who decided to end his life prematurely. He was the leading Estonian Grandmaster in the 90s. At his peak, he reached 2650 ELO and was the 25th ranked player in the world.

His mental issues started in 1996 after he divorced his wife and lost custody of his two sons. Although he was prescribed anti-depressants, the hole he found himself in was too deep. On 17 May 1999, he jumped out of the window of his 4th-floor apartment in Tallinn.

Oll was just 33 at a time.

10) Georgy Ilivitsky

Georgy Illivitsky (Source: tartajubow.blogspot)

No less tragic is the case of a little known Soviet International Master Georgy Ilivitsky. Even though he is virtually forgotten today,6 he was one of the strongest Soviet Masters after World War II. Some of his notable results include third place in the 1955 Soviet Championship (together with Botvinnik, Petrosian and Spassky, just half a point behind Geller and Smyslov and ahead of Keres and Taimanov) and victories in matches over Isaac Boleslavsky (1944), Alexey Suetin (1950) and Ludek Pachman (1956).

Alas, he was unable to make further progress. And life was tough for Soviet masters who didn’t make it to the very top. Ilivitsky didn’t get many opportunities to play outside the Soviet Union and had to gradually give up chess. This feeling of failure and abandonment haunted him during his entire life. When he was 68, he decided life has become unbearable and committed suicide by jumping from the window – apparently inspired by the afore-mentioned Nabokov’s novel The Defense.

11)Pertti Poutiainen

Pertti Poutainen (source: Wikipedia.ru)

Another tragic story reminiscent of Lembit Oll and Georgy Ilivitsky. Pertti Poutiainen was the Champion of Finland in 1974 and 1976. He was awarded the title of International Master in 1976. Alas, according to Boris Gulko 7:

“Poutiainen was a talented player from Finland. He was their chess hope. At this time in my career, I played him twice in the Soviet Union. Alas, the stress of chess tournament life became too great for him and he later committed suicide.”

Poutiainen took his life on June 11, 1978.

Examples such as Oll, Ilivitsky, Poutiainen, Vitolins and Grigoryan show how merciless the system in the Soviet Union was. It was the perfect example of “winner-takes-it-all”, where the top Grandmasters enjoyed great privileges at the expenses of everyone below their level. Evgeny Sveshnikov, one of the most vocal fighters for the rights of chess players also pointed it out. From his Wikipedia page:

Most fundamentally, it is very difficult for chess players to earn a living; he speaks of many chess players in Russia and the Baltic States suffering severe depression and in some cases committing suicide

12) Shankar Roy

Shankar Roy (Source: Kolkata Bengal Info)

The most recent, but no less tragic example of a chess player succumbing to depression is Bengali International Master, Shankar Roy. Roy – an employee of Eastern Railway, represented India in several international competitions and won the senior state championship in four successive years from 1995.

Roy has been suffering from depression for several years and already tried to take his life in the past by setting himself on fire. After the death of his father from blood cancer on April 25, 2012, he made the second attempt and hanged himself from a ceiling using his wife’s scarf.

He was only 38 years old at a time.

FINAL WORDS?

Even though the majority of the examples on this list (apart from Roy Shankar) happened from the past, mental illnesses are very much topical even today. According to pretty much any study out there, depression and anxiety have been on the rise in the world in general. And I think they might also be on the rise in the chess world, with all the pressure revolving winning prizes, chasing norms and making it as a chess professional involved.

Is there something we chess players can do about it?

First of all, we can stop stigmatizing mental disorders. Impairing their significance and looking down upon people who have to deal with them. Stating you seek help because you are depressed should not be considered as a sign of weakness, but on the contrary – a sign of enormous strength.

Secondly and more importantly, the best advice I can offer is to start paying attention to other chess players. 8

Yes, our game is full of peculiar and eccentric people. But as much as they are socially inept, many of them are alone in their misery and crave for human contact.

So go to the hall and talk to people.

Approach that “weird guy” nobody wants to approach.

Analyze with an elderly master and listen to his the stories from his past – as much as you find them boring.

Don’t make fun of lower rated players – especially in youth categories.

Don’t create additional pressure or reprimand anyone for their losses.

Show people you care about them. Especially those who need someone to care about them the most.

Because you never know.

You might save someone’s life.

Source: chessentials.com