All through recorded history, man has sought various ways to pass acquired knowledge and skills to succeeding generations. It is an established fact that the ability or inability to achieve meaningful and sustainable development in any society is tied to its ability to pass knowledge, information, and acquired skills to others within the society and to future generations.

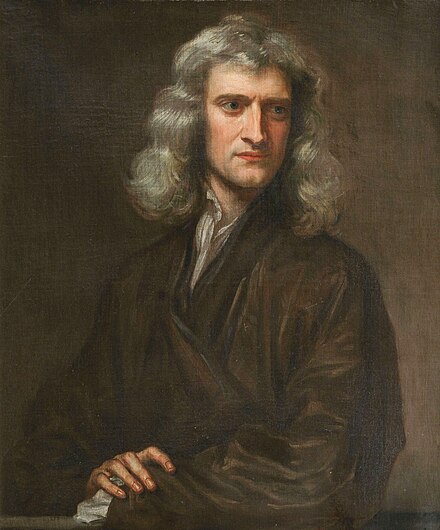

For development to take place, one must study and, as quickly as possible, absorb what has already been ‘established’, then build upon it. It would be a total waste of our time and that of our predecessors to start every process or procedure from scratch.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”— Sir Isaac Newton

In chess, the works of François-André Danican Philidor in the 18th century made it easier for players like Paul Morphy and Adolf Anderssen to develop much more rapidly than they probably would have without his influence. Morphy’s style of play influenced others, and so did Wilhelm Steinitz through his games and published works.

The works and games of Siegbert Tarrasch and Aron Nimzowitsch, the fathers of the hypermodern school of chess, in the early part of the 20th century, paved the way for rapid chess development over the next decades. In fact, most of their teachings would still remain relevant as long as the game of chess endures. These two players radicalized the way chess development and study were viewed. Whether one accepts their scientific approach to the game or not, their well-documented journals ensure a wider grasp and understanding of the chess discipline.

“The best chess player of his day was François André Danican Philidor… His published chess strategy stood for a hundred years without significant addition or modification. He preached the value of a strong pawn center, an understanding of the relative value of the pieces, and correct pawn formations…”— GM Boris Alterman

In the world today, it is arguable that the ‘Western World’ is still ahead in development because they kept, and still keep, better records. The foregoing arguments will probably meet little resistance, if any. Where most of us won’t align will be in our approval/preference of one teaching/training method over another. What is the most efficient way of passing across knowledge and skill in our rapidly evolving world, where concepts, innovations, and products, in certain cases, become obsolete in years, or even months, after hitting the scene? Like every other discipline these days, the chess player has to quickly learn the basics, then constantly update his knowledge; more pertinent now that theory considered accurate decades ago would probably be grossly flawed or inadequate today.

The world record for the youngest chess Grandmaster ever is held by Abhimanyu Mishra, who achieved the feat at 12 years, 4 months, and 25 days. He is now 15 years old.

It is no longer considered a spectacular feat to have a child trained to become a chess grandmaster by age 13! In 1991, Judit Polgár broke Bobby Fischer’s long-standing record by becoming the youngest chess grandmaster in history at 15 years and 4 months. Fischer’s record had stood for 33 years! This was ‘news’ more so because she was female and Bobby Fischer was considered an exceptional genius. Bobby Fischer, though, had the arduous task of being his own personal trainer for the most part. Judit, on the other hand, was homeschooled with chess as her major by her chess coach father. These days, the new normal for becoming a chess grandmaster is 14/15 years of age. In fact, if by 20, one still hasn’t achieved the GM title, he is considered a ‘self-made GM’ – a term reserved for late bloomers, who like Fischer, probably had to organize most of their training/study themselves – if he eventually does attain the title. At 30, most chess players begin to relinquish hope altogether. To produce a GM within the limits of our perceived timetable is therefore something sought by chess coaches the world over. I guess the same, or at least similar ‘time-cages’ plague other fields of endeavor.

“A teaching method comprises the principles and methods used for instruction. Commonly used teaching methods may include class participation, demonstration, recitation, memorization, or combinations of these. The choice of teaching method or methods to be used depends largely on the information or skill that is being taught, and it may also be influenced by the aptitude and enthusiasm of the students.”— Wikipedia.org

What then are the best training method(s)? How do we ensure students get optimal training? Numerous training curricula have sprung up all over. Various studies and researches have been carried out on this matter, mostly inconclusive or conflicting. The truth is, just like I attempted to state in an earlier article, a method that works for one student might fail when applied to another. That is why even when monozygotic twins are subjected to the same environment and training, they still end up slightly different. For training to be effective, it must be subject-specific. This fact notwithstanding, there are definitely certain general methods that work across the board. One of these is actual practice. Someone training to be a world-class player in any sport must play in world-class events or at least simulate them. A child having the world’s best coaches on his team, with the best training materials and conditions, will almost certainly fail if he gets no practical feel of what he is training for. This is more evident in a game as complicated as chess, where psychological and numerous other ‘non-chess’ factors like nutrition, physical fitness, number of hours spent sleeping/resting, marital/relationship status, age, as well as a lot of other mundane and sublime things, have a huge say on a player’s tournament performance.

A trainer must first strive to understand his student and his needs, and only then develop a tailor-fitted regimen. We are all unique creatures, but mostly, man is what he repeatedly does. There is no substitute for practical experience. Personally, I totally believe in the 10,000 Hour Rule: For one to become a Master in any field, he/she must spend a minimum of 10,000 hours on it.

No matter how good the training methods used on a student, his interest level and passion, or the absence of it, will play a major role in his development. The role of mentorship cannot be overemphasized either. The student must have an ‘image’ of that which he wants to become, equal or surpass. Then both the trainer and his student must believe it is attainable. The rest will turn out, as they say, like magic.

Truth be told; there is no magic formula. However, there are methods that work well for most. Once you decipher your student and his training needs, it becomes easier to train him at optimal capacity and speed.